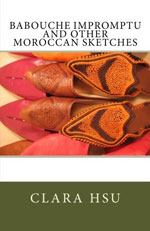

It took some time, and, as Dore said, some webbarizing—meaning solving technical issues on the web without knowing what I was doing. My book of short stories, Babouche Impromptu and Other Moroccan Sketches, has been reissued with more stories and a new look, and it is available now on Amazon.

It took some time, and, as Dore said, some webbarizing—meaning solving technical issues on the web without knowing what I was doing. My book of short stories, Babouche Impromptu and Other Moroccan Sketches, has been reissued with more stories and a new look, and it is available now on Amazon.

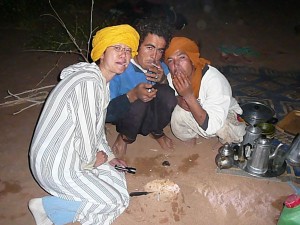

The love story of a Berber and his charge, and a message from the Sahara were added to the collection. Babouche Impromptu opens with an extensive introduction by Jack Foley that included some of my recent poems.

A kindle edition is also available.

I invite you to read the stories, and leave a comment on the “Customer Review” if they move you. Thank you.