Urfa, located in south-eastern Turkey, smells of grilled lamb. It is in the air. Men fanning endless chacoal grills on the streets and placing skewers of cubed meat, liver and heart on the fire. I taste sheep in my lentil soup, rice, and the selections of entree at the locantas. I taste sheep in my saliva.

Urfa, located in south-eastern Turkey, smells of grilled lamb. It is in the air. Men fanning endless chacoal grills on the streets and placing skewers of cubed meat, liver and heart on the fire. I taste sheep in my lentil soup, rice, and the selections of entree at the locantas. I taste sheep in my saliva.

Dore and I watched the owner of an eatery cut up a carcass as we waited for our lunch. His skilled hand massages a long spine, exposing unwanted tendons and cutting them off.

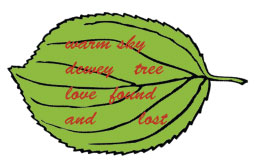

At an open air eatery, four young Kurds who shared my table insisted on paying for my kebap sandwich. I had nothing to give back in return and decided to write a poem for them. One of the men, Abdul Kadir, read my poem out loud: …the world is a small place/when the heart is big. An older man who worked at the eatery smiled and nodded his head. Poets are welcome in Urfa.