Clara Hsu’s first poetic play, Love on the Magpie Bridge, was written for the players of Clarion Performing Arts Center’s Summer Theater, 2019. Based on a Chinese legend known in the celebration of Qixi (Night of Sevens) festival, the play incorporated an ancient poem, a popular folk song, an art song and many classical and folk tunes played on the guzheng by David Wong. With an intergenerational cast the play was performed on August 5, 7 and 11 to the delight of the San Francisco Bay Area community. This year, Night of Sevens falls on August 25. Let us celebrate the festival of women, domestic skills and Mother Nature by watching together this fun and magical play on Youtube!

Tag: Chinese

Blake in Chinese

Inspired to translate after reading a friend’s Chinese translation of this poem:

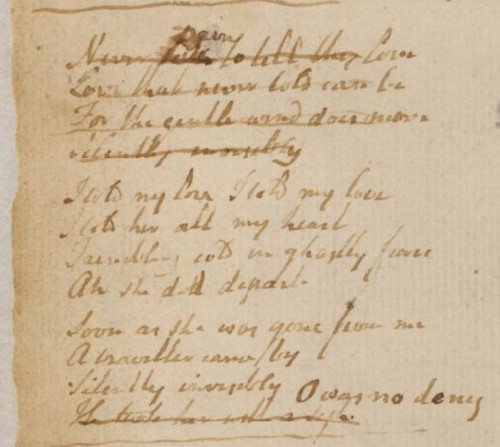

Never Seek to Tell Thy Love

by William Blake

Never seek to tell thy love

Love that never told can be;

For the gentle wind doth move

Silently, invisibly.

I told my love, I told my love,

I told her all my heart;

Trembling cold, in ghastly fears—

Ah! She doth depart.

Soon after she was gone from me,

A traveller came by;

Silently, invisibly

He took her with a sigh.

永不訴說你的愛

不言的愛方能存

因为那和風起動

悄悄地, 無影地

我告訴她, 我告訴她

我訴出我的心

在發抖的冷和恐懼中

啊! 她因此而別

她離開我不久之後

有一個旅人路過

悄悄地, 無影地

一嗟便把她帶走

The Metamorphosis of Su Shi

Don Brennan, Dan Brady and I met weekly at La Boheme Cafe in the Mission several summers ago. We had decided to translate Chinese classical poems. Soon our small group more than doubled in size when friends heard about our endeavor. After a few productive sessions the group slowly turned into a social gathering and nothing of any significance was produced. We disbanded when the summer was over.

Don Brennan, Dan Brady and I met weekly at La Boheme Cafe in the Mission several summers ago. We had decided to translate Chinese classical poems. Soon our small group more than doubled in size when friends heard about our endeavor. After a few productive sessions the group slowly turned into a social gathering and nothing of any significance was produced. We disbanded when the summer was over.

Once in a while I would look at a Chinese poem and decide to translate it. It’s a healthy mental exercise, keeping in mind the compact nature of each Chinese character and trying to find its concise equivalence in English. This week, one line in a Su Shi’s poem reminded me of a line in Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. When put side by side they complimented each other. Now I have arranged lines from various poets of the west to dialogue with Su Shi’s lines. The straight translation has morphed into a poem that is not quite Chinese or English, not East, nor West, but maybe an interesting meeting of minds.

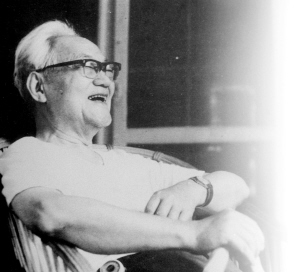

Ba Jin and I

Beside the famous Green Apple Books on Clement Street is a tiny Chinese book shop. I walked in and immediately noticed the odor—familiar, even after over thirty years—Chinese books smell different from English books.

Beside the famous Green Apple Books on Clement Street is a tiny Chinese book shop. I walked in and immediately noticed the odor—familiar, even after over thirty years—Chinese books smell different from English books.

An old man sitting at the front desk was speaking Cantonese on the phone. Only one other customer was browsing. At the “Literature” section I asked for the work of Ba Jin. The old man came over and pointed them out to me. The other customer overheard us and laughed, “Wah, reading Ba Jin?” as if Ba Jin was someone unapproachable.

I walked out of the store with Family, first of Ba Jin’s Torrent triology. Down the street was a typical Chinese bakery. They were bringing sweet and savory pastries fresh out of the oven. I bought a scallion and shredded pork roll and a cup of coffee, then sat down to read.

Two guys came into the pastry shop. They sat behind me and started their conversation, yelling, as if they were hard of hearing. Their yakety-yak on food and gossip was juxtaposed with Ba Jin’s thoughtful and elegant prose. He was an author who lived through the Sino-Japanese War and the Cultural Revolution, until well into the 1980’s.

I left the pastry shop when two more men came in and joined the conversation. Ba Jin and I, well, we were outnumbered.

No Touching

Traditional Chinese custom: men and women don’t touch. We bowed to each other. Hand shaking was considered modern. How did it come to be that touching was prohibited between the sexes? We could not have derived this custom from watching other animals when they copulate in the open.

Traditional Chinese custom: men and women don’t touch. We bowed to each other. Hand shaking was considered modern. How did it come to be that touching was prohibited between the sexes? We could not have derived this custom from watching other animals when they copulate in the open.

Divide and conquer. To suppress the natural response of a body when touched is to submit to bondage. Was it a means for the governing authority to control the mass? And marriage was the license to touch. Who invented marriage?

With my upbringing, it took a long while for me to feel comfortable with the “western” greeting. My college roommate Mayra, who was Cuban, used to make fun of me.

“Don’t be half-hearted, girl. Give me a full-body hug!”

Image taken from en.showchina.org

The Good Wonton

“Go down three blocks on 4th Ave. The hole in the wall place is called Good Taste. My co-worker from Beijing said it’s the best,” said the helpful lady at the door, who sold us tickets to Portland’s famous Chinese Garden.

“Go down three blocks on 4th Ave. The hole in the wall place is called Good Taste. My co-worker from Beijing said it’s the best,” said the helpful lady at the door, who sold us tickets to Portland’s famous Chinese Garden.

After visiting the stunningly beautiful courtyard and gardens, all in traditional Chinese style, we decided to forgo their elegant tea house for the recommended “Good Taste.”

“Good Taste” was indeed a small family establishment. We each ordered wonton soup. My first bite reminded me that I was not in San Francisco. Second bite told me the seasoning was all wrong. When I looked up from my bowl I found my daughter Julia and her boyfriend Brent wolfing down their portions like there was no tomorrow.

“It’s delicious!” cooed Julia. And Brent nodded eagerly in agreement.

The little cloud-like morsels with shrimp and ground pork filling are probably one of the easiest things to make. Yet in this restaurant they tasted like wet Italian meatballs.

“It’s because you’ve forgotten the taste of good wontons,” I said to them. But the real reason, to me, was that they had neglected to put in the secret ingredient: love.

Photo by Arthur Che.

When Li Po Meets Ezra Pound

Stepping into Tranquil Resonance Studio, the hustle and bustle of Chinatown disappeared behind my back. Yellow walls, wood floor, traditional Chinese xuanzhi furniture, brush paintings, tea sets and a row of guqins (seven-stringed zithers) on the wall had the style of an old Chinese study.

David Wong, proprietor, listened to my reading of Li Po’s “Cho-Kan Hang”.

“I think the Fisherman’s Song would work well with this,” David said. He played the tune on the guqin and I read the poem again, first in Cantonese, then a translation in English by Ezra Pound with the title, “The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter”.

All thirty lines of “Cho-Kan Hang” were made up of five syllables. I found it binding and difficult to be expressive.

“In a ‘five syllabic finite poem’,” said David, ” expressiveness is to be derived only from the varied tone of each character.”

The fluid and irregular lines spoken by Ezra Pound’s river-merchant’s wife gave a definite contrast to Li Po’s wistful lady. Reading the poem one after the other, the character was fully realized—she might be confined within four walls, but her feelings knew no bound—by two poets centuries apart.

What We Imagine

“Look what you have done,” The Pig said to the Monkey, “invited an uncombed and unwashed Kwan Yin.” They looked on as Kwan Yin approached, disheveled and barefooted, her robe haphazardly folded together. from Journey to the West

“Look what you have done,” The Pig said to the Monkey, “invited an uncombed and unwashed Kwan Yin.” They looked on as Kwan Yin approached, disheveled and barefooted, her robe haphazardly folded together. from Journey to the West

I read this classical Chinese novel as a child and this is one of the passages that has remained with me. Kwan Yin, the revered Goddess of Mercy appeared like an ordinary person hurrying to solve a crisis after being woken from sleep. She was sensual, soft with her hair down and her face freed of make-up. This moment was observed by the Pig and with that, animal, human and goddess all came down to the same level.

A friend and I talked about subtlety in writing, how it gives room to the readers to imagine for themselves. It is what I imagine that I remember.

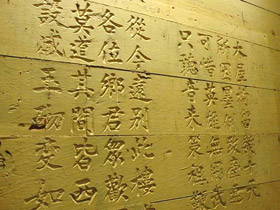

Poems On Walls

It was a bright sunny day in 2003 when my cousin Ronald and I took the ferry to Angel Island. Ronald was visiting from Flint, Michigan, and was curious about my newfound passion in poetry. I told him what I know about the Immigration Station on Angel Island, that between 1910-1940, many Chinese immigrants were detained on the island while their papers were being processed. Squalid conditions, humiliation, anxiety of deportation and hopelessness led to sickness and suicides. Desperate for an outlet, the detainees carved poems on the walls.

A short hike from the ferry dock led us to the Immigration Station. The lush vegetation, blue sky and bird songs were the making of paradise. I could not imagine suffering in such a pristine setting. We entered the living quarters. The floorboard and the walls seemed to be made of paper. Just things now, photos, information, artifacts…they did not stir me as I had expected to be stirred. And then I saw the poems on the walls. Most of them barely legible. But there they were, emerged from layers of old paint, reaching out, warning, reminding, retelling the inhuman treatment from one people to another. After three-quater of a century these words still carried a haunting vibration in the absence of their authors.

Ronald and I were quiet on our way back. Despite the gorgeous day, our hearts were heavy.