To understand the construct of a poem is to dive into the form and play with it. Like Leggos, take individual pieces, put them together. If the result doesn’t please you, pull them apart and rearrange.

To understand the construct of a poem is to dive into the form and play with it. Like Leggos, take individual pieces, put them together. If the result doesn’t please you, pull them apart and rearrange.

The good thing about writing daily is that you accumulate lots of materials. Half-baked poems, one liners, singular words; they may be useful sooner or later.

Amy Clampitt in the Paris Review said she revised a poem up to twenty-six times. Mary Oliver: forty to fifty drafts. Did they save every scrap of revision? Were they counting? How did a poem emerge and change through all the manipulations? Was the sense of play always present?

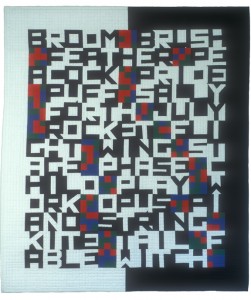

“Word Play” by Jill Ault.

Revision is the Puritan notion of how to write a poem. I remember Robert Bly talking about how he kept rewriting a piece, and each time it failed. He tried and tried and failed and failed. He expected us to admire him for this and to see him as a Serious Poet because of it. Poetry is HARD WORK. (Puritanism.) Personally, I wondered whether, if he was failing that much, he was in the wrong line of work. If you keep failing, mightn’t the reason be that you should be doing something else? Can you imagine a carpenter saying, “I kept trying to make that chair, and each time I failed. One time I put the leg in upside down. One time it all wobbled.” That’s not much of a carpenter. What about Joy–not Effort–as the center of the artistic enterprise? “Only when I glee,” wrote James Broughton, “Am I me.”